The Wishing Well

Art Basel Statements

With PSM

Booth M16, Hall 2.1|

June 19-22 2025

The Wishing Well begins with a personal memory of a fallen birch tree, reimagined as a vessel that probes materiality and the enduring myth of purity often projected onto nature. Long regarded in the West as a symbol of innocence and sublime beauty, the birch here is recast as a porous, hybrid body shaped by contamination, entanglement, and multiplicity. Reflecting on the tree’s culturally saturated history, from European Romanticism and nationalist iconography to the Indigenous practices of the Anishinaabe and the Sámi, the work refuses singular meaning. The birch becomes an emptied monument; a spectral void where histories, memories, and bodies intermingle, mutate, and come undone.

Constructed from two hollow plywood forms clad in a patchwork of sustainably harvested bark from Siberian forests and remnants of fallen German trees, the work exudes a Frankenstinian charm. Graphite scribbles, oil pastel, charcoal powder, and pyrographic inscriptions akin to asemic writing—a wordless, open semantic form of script—dissolve into the bark’s paper-like skin. Earrings and shards of a personal body mirror glint across the surface like betulin, the crystalline compound responsible for the birch’s luminous, heat resistant sheen. Through this meticulous intervention, the bark becomes a site of concealment and revelation, destabilizing the tree’s symbolic legibility and prompting a closer look. The Wishing Well is thus a site of unmaking, inviting us to consider what remains when structures of meaning are hollowed out.

The birch’s Proto-Indo-European etymology bherə-, “to shine” or “to be white” hints at a long entanglement with notions of purity and progress. In Romantic landscape painting and literature, the tree’s slender, pale trunk was often feminized and racialized, reinforcing gendered essentialisms around motherhood and domesticity, as well as naturalizing ideals of whiteness. As Europe industrialized, this imagery was swiftly folded into various nationalist projects, eventually making the birch the national tree of Finland, Russia, and Sweden, while retaining deep cultural resonance across the continent.

In some Indigenous worldviews in North America and Scandinavia, the birch is not only a symbol, but also a collaborator; a being whose bark becomes baskets, tinctures, flour, and canoes, and whose vitality is honoured through practices of reciprocal care. From this vantage point, the birch’s Western ecological classification as a “colonizer” or “pioneer” species due to its rapid growth is reframed, not as an agent of domination, but of renewal in disturbed ecosystems. Here, survival is collaborative, not competitive; contamination is not decay, but transmutation. The Wishing Well channels this ethic, offering a poetics of disassembly.

The installation also features a carved tree stump that doubles as an interactive mancala board, complete with 48 handmade ceramic beads—a tribute to a beloved game from childhood. Broken breezeblocks from a previous installation and mirror fragments quietly accumulate in the tree’s hollow like coins at the bottom of a well. Oil paintings rendered on birch bark depict conjoined landscapes of fragmented bodies and water bodies bordered by nations with deep cultural ties to the tree. And just out of the frame, a poem faintly hums.

Amid the fair’s spectacle, The Wishing Well reads as both an elegy and an invocation. A fractured tree carcass singed in charcoal and strewn across white bathroom tiles inevitably conjures an uncanny vision of total environmental collapse. The birch here is not pure, not sanctified; it is wounded, interdependent, and clinging to life. In a world obsessed with borders, clarity and control, the project insists that the most generative forms of beauty and survival emerge from muddied waters.

— Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju, 2025

Installation Image Credit: Ivan Erofeev

None of us understood that the body is a connected thing (Rügen, Sea of Azov, Hanko Beach, The Boundary Waters - Anishinaabe Land, Stora Sand), 2025, 165.5 x 20 cm, oil, graphite, and pyrography on birch bark

None of us understood that the body is a connected thing (Self portrait Series), 2025, dimensions variable, oil, graphite, and pyrography on birch bark

Paintings Image Credit: Eric Tschernow

Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju: BloodLetter

Kestner Gesellschaft

Hanover, Germany

December 7, 2024 - March 2, 2025

BloodLetter is the first institutional solo exhibition by the Nigerian-American artist Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju. At its heart is the artist’s book of the same name, a handcrafted leather-bound work made specifically for the show at the Kestner Gesellschaft. This book forms the conceptual core of the exhibition and embodies key motifs that shape the artist’s practice: ancestry, memory, grief, healing, and the complex connection between individual and collective narratives.

Serving as much more than a collection of texts, BloodLetter functions as a personal archive. Poems, essays, letters, and journal entries address questions of identity, belonging, and migration: autobiographical reflections intertwine with universal themes including intergenerational trauma and resilience, familial ties, and cultural transformation. The book is presented in the exhibition within a specially designed installation made of clay elements called “breeze blocks,” inspired by the cement blocks used by her grandfather in the construction of his home. This pavilion creates an intimate space within the exhibition itself, both protective and porous, while also highlighting the artist’s book as both a physical and conceptual center of the exhibition.

The exhibition focuses on Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju’s large-scale paintings on leather and small sculptures made of birch, whose symbols and personal motifs expand the thematic range of the exhibition. Ilupeju combines painting, installations, and text in her practice, making visible the fractures and overlays of memory through unconventional media and surfaces modified with scratch marks and pyrographic techniques. Her works link personal and collective narratives, questioning traditional archiving while opening spaces where stories can be told in depth. In particular, the relationships with her family and thoughts on homeland and diaspora are a common thread throughout her works.

The title BloodLetter refers on one hand to the central role of blood as a metaphor in Ilupeju’s work. For the artist, blood signifies life, connection, trauma, and the transmission of stories. On the other hand, “Letter” points to recorded written and spoken language, asemic writing, the documentation and reshaping of narratives. Together, the interplay of these ideas creates an artistic concept that explores the relationship between body, language, and history.

Curator: Alexander Wilmschen

Image credit: Volker Crone

BloodLetter

PSM

Berlin, Germany

September 6 - November 9 2024

The exhibition BloodLetter by Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju at PSM consists of 9 new paintings in oil on leather, as well as 4 works on canvas and Birch tree bark, and an accompanying collection of texts. In this new body of work, she references and alters source photographs pulled from personal and family archives, as well as found images, to process residual feelings and questions around ancestral belonging, homecomings and homegoings, memory, grief, and the beauty amidst it all. A text by José B. Segebre further enriches the exhibition. Full Exhibition Text

On the occasion of Berlin Art Week, on Saturday September 14th at 7pm, Monilola held a reading of the texts conceived around the exhibition’s themes.

Image Documentation: Eric Tschernow

Saint V.

Saint V.curated by Miriam Bettin

Tarte Vienna / Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman

Vienna, Austria

Oct. 6 – Nov. 24 2023

V.

as in Venus

as in Vision

as in Voice

as in Visitor

as in Veronica

as in Virgin Mary

as in Void

Saint V. is the first solo exhibition of Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju in Austria and brings together a new body of work.

The eponymous oil painting Saint V. (2023) portrays Ilupeju’s mother at 21, the age she migrated from Oyo State, Nigeria to Maryland, United States. Raised in an interfaith family between Islam and Christianity, Ilupeju’s work explores religious iconography and the link between creative process and spiritual salvation.

Through painting, writing and installation, Ilupeju re-visits personal places and objects to reconfigure their forms and contents. Expanding on the classic genre of the nude self-portrait, as in the life-size cut out figure In the Light of Day (2023), the artist is drawn to intimate found objects (Black Hole, 2023) as carriers of embodied memory, history, and energy.

Ilupeju’s recent use of recycled leather (Collateral, 2023, Lost Hiker, 2023, All The Way, 2023) as painting surfaces stems from the same interest with enlivened materials. The meditative scribbles and scratches on a discarded, deconstructed and pierced leather backpack, which the artist carried throughout her adolescence, serve as a portal to connect moments in time and modes of being. Reminiscences are inscribed into the resilient animal skin, understanding scars as traces of growth rather than wounds. Pale of Crabs (2023), so the title, refers to the tragic parable of a crab trying to crawl out of a bucket, only to be pulled back down by its own species. In another light, the piece refers to vulnerability of the backpack which, despite having long ago lost the drawstrings that kept it closed, never had an item lost or stolen; a reminder of the virtues of open-heartedness and that things are held together even without one's control.

Crucifixion (2023) presents a transcendental state of body and mind in which the nude figure dissolves into the void. It is a void that is more than the end or nothingness. Rather, it is a void that opens up new possibilities and reactivates what Audre Lorde would describe as follows:

“Sometimes we drug ourselves with dreams of new ideas. The head will save us. The brain alone will set us free. But there are no new ideas still waiting in the wings to save us as women, as human. There are only old and forgotten ones, new combinations, extrapolations and recognitions from within ourselves–along with the renewed courage to try them out.” –Audre Lorde, Poetry Is Not a Luxury, 1985

The void is a space of uncertainty but also of transformation. Ilupeju’s works have the transgressive potential to turn loss and discomfort into beauty, to befriend the unknown, and to ultimately fill the void with renewed ideas and restored faith.

Watch out. Your backpack is open.

Text: Miriam Bettin

Work List

Image credit: Galerie Thoman / KunstDokumentation.com

Hands Full of Air

10.12.20 – 28.03.21

at Galerie im Turm in Berlin, Germany

Where do the edges of the individual end and those of the community begin? How can this reflexive relationship be used to recover knowledges and techniques that can resist and transmute the corruptions of oppressive systems?

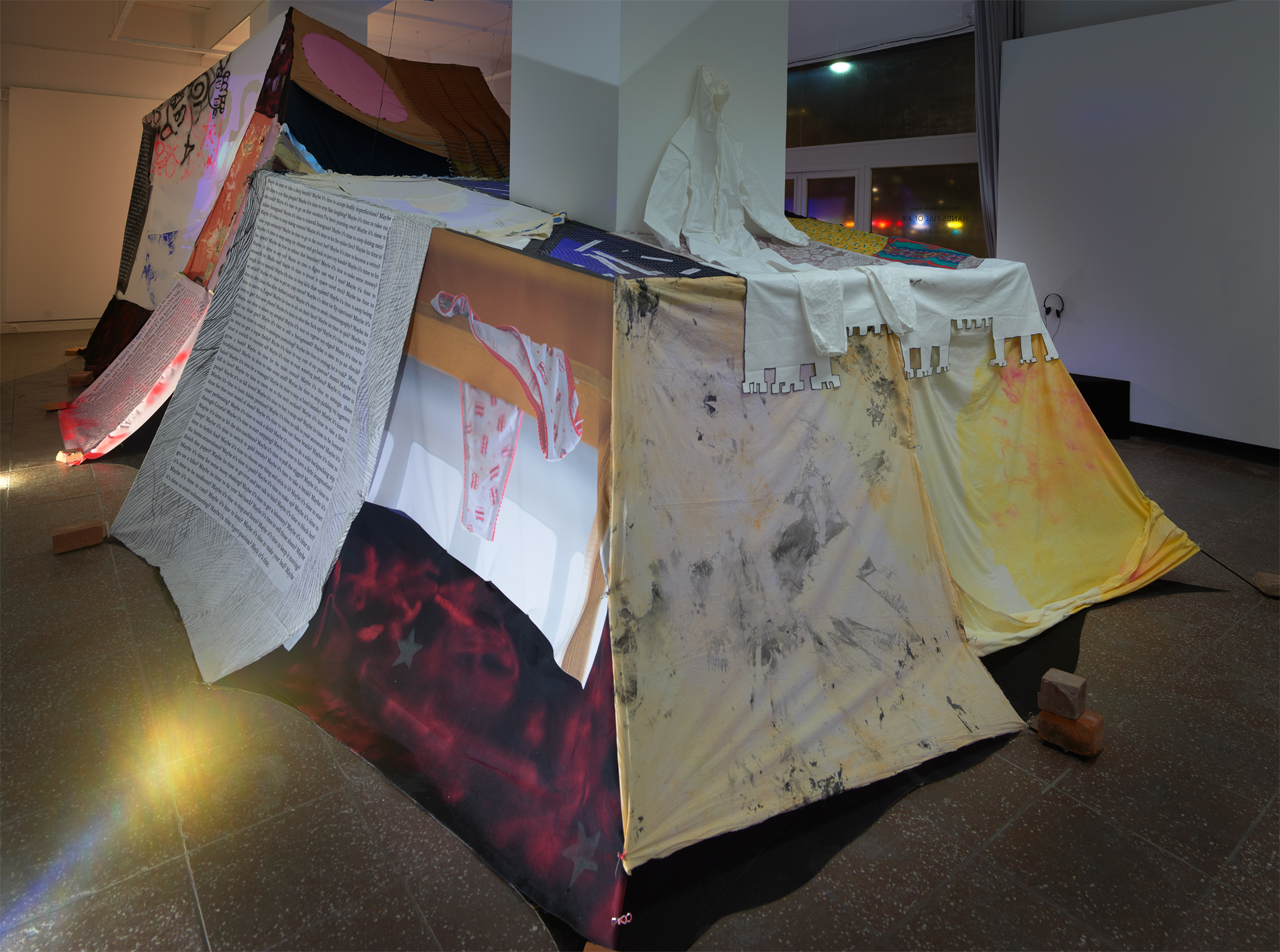

In Hands Full of Air, Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju explores intuition and vulnerability as a starting point for a practice of collective care. Influenced by the ephemeral nature of blanket forts, the immersive installation comprises altered bedsheets and textiles contributed by her friends and artists from around the world. Each piece embodies an affective moment, a trace of intimacy, or a gesture of love. Into this collaborative support structure, Ilupeju weaves her own videos, paintings, fabrics and objects, in which she examines the formation of the self within constructed epistemologies of sexuality, history, and representation.

Ilupeju’s work is an attempt to dwell in the ambivalent space between exposure and isolation, to find recognition in the discomfort of shared vulnerabilities. By blurring the lines of authorship and borders, the artist reflects on the constitution of identity and on empathy as a tool of resistance. The subversion of the fort structure demonstrates the ways in which collective fragility and porosity can generate spaces where different forms of seeing and listening unfold and where vulnerability is transformed into resilience and self-empowerment.

WITH FABRIC CONTRIBUTIONS BY Sharmeen Anjum, Peter Basma-Lord, Anguezomo Mba Bikoro, Lu Rose Biltucci, Ellie Lizbeth Brown, Federica Bueti, Lucia Pedroso Cabrera, Olivia Chou with Ally Zhao, Binta Diaw, Nathan Storey Freeman, Bambi Glass, Danny Greenberg, Riya Hamid, Nile Harris, Samhita Kamisetty, Avantika Khanna, Byron Kim, Eleanor Kipping, Beverly „KöTA WALi“, Kelly Krugman, Cooper Lovano, Markues, Adam Milner, Emily Velez Nelms, Luiza Prado, Thomias Radin, Elliot Reed, Djibril Sall, Lorenzo Sandoval, Lili Somogyi, among others.

Curated by Jorinde Splettstößer

View fabric contributions here. Photos by Raisa Galofre

Interview with Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju about Hands Full of Air, by Mayra A. Rodríguez Castro

TEAM

CURATOR Jorinde Splettstößer

CO-CURATOR Linnéa Meiners

CURATORIAL ASSISTANCE Sofía Pfister

HEAD OF PRODUCTION Carolina Redondo

INSTALLATION ARCHITECTURE Benjamin Busch

INSTALL TEAM Claudio Aguirre, Johann Hackspiel, Felipe Monroy, Benjamin Thomas

PROJECT ASSISTANCE Dani Hasrouni, Sophie Lösch, Sophie McCuen-Koytek

TRANSLATIONS Saskia Köbschall, Sophie McCuen-Koytek

GALLERY SUPERVISION Ferdinand Gieschke, Daniel Noack

ARTIST THANKS

This exhibition is dedicated to my dear friend Byron Kim (1997-2020). My gratitude is endless and you are in my heart always.

As this project was motivated by the desire to more deeply understand the ties between individuals and their communities, it would not have been made possible without the people who I am lucky to call my friends, supporters, collaborators, and inspirations.

I want to thank Merilyn Chang, Mayra Rodríguez Castro, Anguezomo Mba Bikoro, Federica Bueti, Morgan Gu, Markues Aviv, Raisa Galofre, Luiza Prado, and the other artists and friends who, by contributing their piece of fabric or sharing their perspective on the subject, entrusted me with an intimately architectural part of my installation.

I would also like to send my deepest thanks to Richie Kim and the Kim Family for giving me the space to honor Byron’s memory through this show and Emily Castronuovo for so kindly sending me the piece from New York that Byron had been working on for the installation. My gratitude extends to my loving parents who have shown their unwavering support of my artistic practice since the beginning, as ambiguous as it can seem at times.

Thank you to Benjamin Busch and Lorenzo Sandoval, the team at The Institute for Endotic Research — TIER, for giving me the space to develop this work during my process-based exhibition Eve of Intuition earlier this year. I am also so appreciative to the Head of Production Carolina Redondo and her mounting team for making the install of this work such a laughter-filled, synergetic experience. And lastly, I would like to thank my curator Jorinde Splettstößer and the Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien team for the invitation and support in realizing Hands Full of Air. This project was a labour of love to say the least, and I am so honoured to have been able to share it with all of you.

Installation Photos: Eric Tschernow